Orgogliosi di essere pazzi di Domenico Fargnoli Mad Pride: a Torino hanno sfilato , a metà giugno, il giorno dopo il Gay Pride i “matti” in un corteo aperto dalla sagoma di Marco Cavallo, il simbolo della “liberazione ” basagliana. Il Mad Pride è stato un calendario di eventi fra cui una rassegna teatrale con ”artisti psichiatrici”.La finalità è stata quella di creare uno scambio fra due realtà (quella dei “normali” e quella dei “folli”) per rivendicare la libertà di vivere il disagio mentale “senza essere emarginati, sedati o rinchiusi”. Obiettivi, con le dovute precisazioni, condivisibili: è giusta la lotta contro la segregazione, l’emarginazione e la stigmatizzazione del malato di mente, contro la sopravvalutazione , ma anche la negazione della sua pericolosità. La volontà di incontro non sempre è capacità di viverlo: dove si trova la “follia”? In quanto realtà mentale quest’ultima non è in uno spazio esterno individuabile. La pazzia è molto più presente negli interstizi della normalità che nelle istituzioni psichiatriche. E’ fuorviante ritenere che la liberazione dalla malattia mentale si limiti alla circolazione di malati etichettati come tali nei viali di una città invece di segregarli in un un manicomio . L’espressione Mad pride inoltre , coniata a calco su Gay pride crea problemi su entrambi i fronti. Gli omosessuali o trasgenders rifiutano infatti la diagnosi per cui non si capisce perchè dovrebbero essere accostati ai malati. I “matti” che si vogliono sentire liberi di esserlo si credono nati in un certo modo, analogamente agli omosessuali , e nessuno potrebbe pretendere di modificare una condizione rivendicata con orgoglio: l’unica cura sarebbe la libertà di essere come si è. Si stabiliscono così equivalenze e si confondono pericolosamente realtà che solo apparentemente sono sovrapponibili. L’idea dell’incontro fra normalità e pazzia non è una novità ma risale alla controcultura degli anni 60-70 del secolo scorso . Recentemente è uscito un romanzo Rehab blues di Adrian Laing quinto figlio, di dieci avuti da quattro donne, di Ronald Laing, famoso “antipsichiatra” Inglese. Il libro è una ricostruzione letteraria di ciò che avveniva nei networks della Philadelphia Association fondata a Londra da Laing e Cooper: persone normali fra cui psichiatri, convivevano in comunità residenziali , con altre affette da patologie mentali anche gravi senza preoccupazioni di ruoli e di gerarchie. In un’ intervista a La stampa Adrian Laing parla del rapporto fra Franco Basaglia ed il padre non particolarmente caloroso, nonostante i punti di contatto.

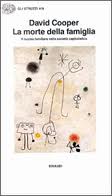

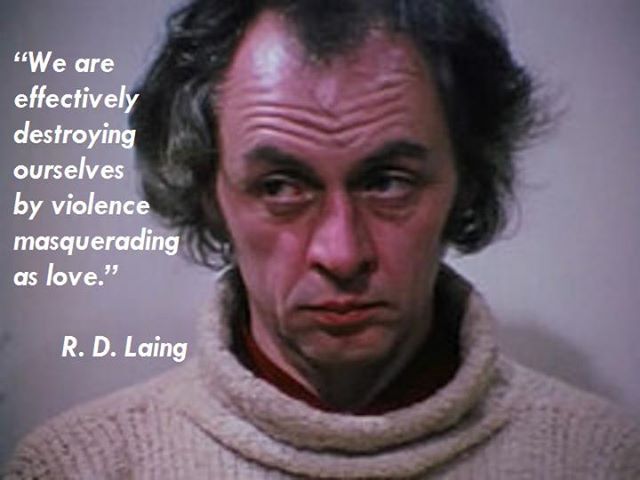

Orgogliosi di essere pazzi di Domenico Fargnoli Mad Pride: a Torino hanno sfilato , a metà giugno, il giorno dopo il Gay Pride i “matti” in un corteo aperto dalla sagoma di Marco Cavallo, il simbolo della “liberazione ” basagliana. Il Mad Pride è stato un calendario di eventi fra cui una rassegna teatrale con ”artisti psichiatrici”.La finalità è stata quella di creare uno scambio fra due realtà (quella dei “normali” e quella dei “folli”) per rivendicare la libertà di vivere il disagio mentale “senza essere emarginati, sedati o rinchiusi”. Obiettivi, con le dovute precisazioni, condivisibili: è giusta la lotta contro la segregazione, l’emarginazione e la stigmatizzazione del malato di mente, contro la sopravvalutazione , ma anche la negazione della sua pericolosità. La volontà di incontro non sempre è capacità di viverlo: dove si trova la “follia”? In quanto realtà mentale quest’ultima non è in uno spazio esterno individuabile. La pazzia è molto più presente negli interstizi della normalità che nelle istituzioni psichiatriche. E’ fuorviante ritenere che la liberazione dalla malattia mentale si limiti alla circolazione di malati etichettati come tali nei viali di una città invece di segregarli in un un manicomio . L’espressione Mad pride inoltre , coniata a calco su Gay pride crea problemi su entrambi i fronti. Gli omosessuali o trasgenders rifiutano infatti la diagnosi per cui non si capisce perchè dovrebbero essere accostati ai malati. I “matti” che si vogliono sentire liberi di esserlo si credono nati in un certo modo, analogamente agli omosessuali , e nessuno potrebbe pretendere di modificare una condizione rivendicata con orgoglio: l’unica cura sarebbe la libertà di essere come si è. Si stabiliscono così equivalenze e si confondono pericolosamente realtà che solo apparentemente sono sovrapponibili. L’idea dell’incontro fra normalità e pazzia non è una novità ma risale alla controcultura degli anni 60-70 del secolo scorso . Recentemente è uscito un romanzo Rehab blues di Adrian Laing quinto figlio, di dieci avuti da quattro donne, di Ronald Laing, famoso “antipsichiatra” Inglese. Il libro è una ricostruzione letteraria di ciò che avveniva nei networks della Philadelphia Association fondata a Londra da Laing e Cooper: persone normali fra cui psichiatri, convivevano in comunità residenziali , con altre affette da patologie mentali anche gravi senza preoccupazioni di ruoli e di gerarchie. In un’ intervista a La stampa Adrian Laing parla del rapporto fra Franco Basaglia ed il padre non particolarmente caloroso, nonostante i punti di contatto. Come si evince anche dalla biografia che Adrian Laing pubblicò nel 1994 l’esperienza di Kinsdley Hall, la più famosa delle households frequentata dal padre fu un vero disastro. Laing più che la pazzia altrui aveva incontrato la propria: il fallimento del traning analitico alla Tavistock aveva accentuato la sua instabilità psichica e favorito l’abuso di alcool e di tutti i tipi di droghe fra cui l’LSD sperimentato in modo intensivo su se stesso e sui pazienti. Basaglia con la moglie dedicò un libro a “Ronnie”: La maggioranza deviante (1971). Nel titolo veniva riassunto un principio dell’antipsichiatria. Secondo una metafora, suggerita da Laing, se uno stormo di uccelli vola in una direzione e due o tre uccelli volano in senso opposto , solo questi ultimi vanno nel senso giusto : i veri de-vianti sono gli altri. David Cooper intervistato dai Basaglia dice: <<(…)La finalità [dei networks alternativi]consiste nel trovare il modo di integrare la pazzia nella società.(…) se qualcuno “impazzisce” può farlo con sicurezza, senza interferenze psichiatriche>> L’Antipsichiatria basagliana non condivise gli eccessi e le utopie comunitarie di quella inglese ma sviluppò anch’essa una opposizione radicale alla psichiatria come pratica e teoria clinico-scientifica senza intraprendere una ricerca propria ed alternativa. La malattia rimaneva un quid residuale e misterioso dopo l’abbandono delle categorie classiche della schizofrenia e delle psicopatie ritenute astrazioni finalizzate a stigmatizare e difendere la norma sociale. Coerentemente con la sua ideologia religioso-libertaria Laing rompe i ponti con la psichiatria. Dopo la chiusura traumatica di Kindsley Hall nel 1970, Laing ebbe un episodio mistico-autistico da cui non si riprenderà : si recò in India mel 1971. In quello stesso anno Massimo Fagioli scrisse Istinto di Morte e conoscenza, edito l’anno dopo, elaborando una nuova teoria sulla realtà umana che renderà possibile, attraverso una prassi terapeutica collettiva che dura ininterrotta da quasi quarant’anni, la cura della malattia mentale ed il superamento delle tradizionali concezioni psicopatologiche. Laing visse per sei mesi in meditazione con un vecchio saggio che , nudo , si avvogeva nella sua lunghissima capigliatura per riscaldarsi. Lì nacque l’immagine del “guru” immortalata dalla rivista Life che lo ritrasse in una posizione yoga, lì inizia il declino di un personaggio carismatico minato da un subdolo deterioramento mentale. Niente più successi editoriali ma solo citazioni di se stesso e debiti :l’alcool e le droghe intaccavano la salute fisica mentre “Ronnie” portava a fondo la distruzione dell’identità medica e psichiatrica. Proprio colui che aveva sostenuto che la famiglia è alla base della patologia mentale aveva reso le sue un inferno.Uno dei suoi figli morì probabilmente suicida mentre una figlia ebbe un episodio schizofrenico . Due anni prima della morte improvvisa per infarto a sessantadue anni, l’Ordine dei Medici Inglese sospese Laing dall’esercizio della professione per violazioni deontologiche.

Come si evince anche dalla biografia che Adrian Laing pubblicò nel 1994 l’esperienza di Kinsdley Hall, la più famosa delle households frequentata dal padre fu un vero disastro. Laing più che la pazzia altrui aveva incontrato la propria: il fallimento del traning analitico alla Tavistock aveva accentuato la sua instabilità psichica e favorito l’abuso di alcool e di tutti i tipi di droghe fra cui l’LSD sperimentato in modo intensivo su se stesso e sui pazienti. Basaglia con la moglie dedicò un libro a “Ronnie”: La maggioranza deviante (1971). Nel titolo veniva riassunto un principio dell’antipsichiatria. Secondo una metafora, suggerita da Laing, se uno stormo di uccelli vola in una direzione e due o tre uccelli volano in senso opposto , solo questi ultimi vanno nel senso giusto : i veri de-vianti sono gli altri. David Cooper intervistato dai Basaglia dice: <<(…)La finalità [dei networks alternativi]consiste nel trovare il modo di integrare la pazzia nella società.(…) se qualcuno “impazzisce” può farlo con sicurezza, senza interferenze psichiatriche>> L’Antipsichiatria basagliana non condivise gli eccessi e le utopie comunitarie di quella inglese ma sviluppò anch’essa una opposizione radicale alla psichiatria come pratica e teoria clinico-scientifica senza intraprendere una ricerca propria ed alternativa. La malattia rimaneva un quid residuale e misterioso dopo l’abbandono delle categorie classiche della schizofrenia e delle psicopatie ritenute astrazioni finalizzate a stigmatizare e difendere la norma sociale. Coerentemente con la sua ideologia religioso-libertaria Laing rompe i ponti con la psichiatria. Dopo la chiusura traumatica di Kindsley Hall nel 1970, Laing ebbe un episodio mistico-autistico da cui non si riprenderà : si recò in India mel 1971. In quello stesso anno Massimo Fagioli scrisse Istinto di Morte e conoscenza, edito l’anno dopo, elaborando una nuova teoria sulla realtà umana che renderà possibile, attraverso una prassi terapeutica collettiva che dura ininterrotta da quasi quarant’anni, la cura della malattia mentale ed il superamento delle tradizionali concezioni psicopatologiche. Laing visse per sei mesi in meditazione con un vecchio saggio che , nudo , si avvogeva nella sua lunghissima capigliatura per riscaldarsi. Lì nacque l’immagine del “guru” immortalata dalla rivista Life che lo ritrasse in una posizione yoga, lì inizia il declino di un personaggio carismatico minato da un subdolo deterioramento mentale. Niente più successi editoriali ma solo citazioni di se stesso e debiti :l’alcool e le droghe intaccavano la salute fisica mentre “Ronnie” portava a fondo la distruzione dell’identità medica e psichiatrica. Proprio colui che aveva sostenuto che la famiglia è alla base della patologia mentale aveva reso le sue un inferno.Uno dei suoi figli morì probabilmente suicida mentre una figlia ebbe un episodio schizofrenico . Due anni prima della morte improvvisa per infarto a sessantadue anni, l’Ordine dei Medici Inglese sospese Laing dall’esercizio della professione per violazioni deontologiche.

La malattia mentale, di cui alcuni sarebbero orgogliosi. non solo esiste ma ti segue perfino fuori dai manicomi uccidendo subdolamente se non adeguatamente affrontatae e curata . Anche David Cooper morirà a soli 54 anni alcoolizzato. Gli organizzatori del Mad Pride dovrebbero non ripetere passate esperienze e comprendere che ci sono “cattivi maestri” che sulla via dell’incontro con la follia è molto pericoloso seguire.

La malattia mentale, di cui alcuni sarebbero orgogliosi. non solo esiste ma ti segue perfino fuori dai manicomi uccidendo subdolamente se non adeguatamente affrontatae e curata . Anche David Cooper morirà a soli 54 anni alcoolizzato. Gli organizzatori del Mad Pride dovrebbero non ripetere passate esperienze e comprendere che ci sono “cattivi maestri” che sulla via dell’incontro con la follia è molto pericoloso seguire.

Interessante testimonianza di un paziente di David Cooper che ci fa comprendere il clima degli anni 60-70 e descrive un modo molto singolare di esercitare la psicoterapia fra camere da letto, bevute e racconti di performances sessuali. In-treatments a confronto è una bazzecola.

Far out

It was the 60s and acid was king. It was hip to be mad and cool to be crazy, and twice a week, for four years, David Gale spent an hour with an eminent psychiatrist, trying to get his head around his own personal terrors. Only the shrink was on a trip of his own…

-

David Gale

- The Guardian, Saturday 8 September 2001

| Brother Beast: A Personal Memoir of David Cooper1Stephen Ticktin |

|||

David will probably be best remembered here in England as the champion in the 60’s and early 70’s of ‘antipsychiatry’, a word he, himself, coined in 1966. The term referred to that movement which began by challenging the medical concepts and practices of the modern psychiatric system — in particular the notion of mental illness itself — and looked for alternative ways of understanding human experience and behaviour and responding to human distress. David himself was instrumental, in 1962, in setting up a very radical venture, within the context of the NHS, at Shenley Hospital, which became known as Villa 21. This was a separate unit in which many young people, who had been diagnosed ‘schizophrenic’, were allowed to live without the interference of potentially harmful drugs, electroshock, or other organic therapies. The unit was run on egalitarian lines, and there was a deliberate attempt to abolish the traditional hierarchy between doctor and patient. Attentive non-interference was the ideal that was aimed for. At about the same time, in 1965, David, along with R.D. Laing, Aaron Esterson and four other like-minded individuals founded the Philadelphia Association, a registered charity that was eventually to set up a number of houses in the Greater London community where people in distress could go and live as an alternative to the traditional psychiatric hospital. He continued his involvement with the latter association until 1971 when he left England (early 1972) for Argentina. I first met David at this particular juncture of his life. He was en route to Argentina. He had been invited to participate in a week-long conference on ‘madness’ by the Health Advisory Service of our university (Toronto, Canada). I was a third-year medical student at the time and was supposed to be attending seminars in obstetrics and gynecology. However a ‘Madness Conference’ and a chance to meet David could not be passed by so easily, and so I attended the whole event. I had already read several of his books (as well as a few by his colleague R.D. Laing) and his existential Marxist writings both excited and catapulted me out of my more mechanical Freudian orientation. David soon appeared in full splendour. He was a large, wildlooking man with long golden locks and a huge red beard. He was dressed in black garb and had a big llamaskin coat of the same non-colour that lent him a beast-like quality. (Ironically, later on, I discovered that he often used the word ‘beast’ as a term or endearment!). But his blue eyes were very gentle and he spoke in a soft voice. And he was extremely thoughtful. One had the impression, almost immediately, of being in the presence of an exceptionally deep and beautiful man. When it came his turn to speak, he started by introducing me and saying that I would play a song. We had met only three hours previously, and, at that time, he had heard me playing my guitar. He had then asked me if I would play something at the debate and I agreed. I chose Bob Dylan’s ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’ (There’s something happening here but you don’t know what it is do you Mr.Jones). It set the tone for what David wanted to say, I didn’t realise it, at the time, but this was actually the beginning of a pattern that would repeat itself many times over as we travelled together, over the next few years, from one country to the next, with me playing a song and David speaking. He spoke most bravely that first time. He was inebriated and initially addressed that English-speaking audience in French, thinking that he was in the province of Quebec. He made it clear that he had left England, left the Philadelphia Association, and was no longer collaborating with Laing and Co. The latter, he said, was on a spiritual trip. He, David, was on a political one. At one point in the debate he actually left the podium and sat in the audience — I believe to underscore the idea that in the field of ‘madness’. (He used to say, often, at that time, that ‘schizophrenia’ did not exist but ‘madness’ did), there were no experts, and that one needed to remain sceptical of the so-called ‘science’ of psychiatry. I thought for all his appearance as a ‘guru’ that he showed a tremendous humility and compassion and it was these qualities in him which struck me the most. One woman in the audience summed up the whole experience in a nutshell: “He has a heart of gold” she said. Over the next three to four years I spent quite a bit of time with David, culminating in our sharing a flat for a year in Crouch End, London (1974). It was to prove to be his last year in England. He had returned from his sojourn in Argentina a few months earlier, and when I joined him I found him to be in a state of complete despair. He was drinking heavily and had virtually severed all his links with his former colleagues in the Philadelphia and Arbors Associations. Although he saw his family from time to time, relations were tense. It seemed that Laing and his followers had embarked on a course of exploring and utilising various therapies of the mind, body, and spirit, whereas David, in spite of a brief period in private practice in Harley Street in the late 60’s had, by this time renounced the latter occupation, primarily for political reasons. He was wont to say at the time that there were no personal problems only political ones. So we lived frugally during this period, and I acted, in a funny sort of way, as the intermediary between David and the outside world, answering telephone calls and letters, and arranging interviews and conference meetings when desired. His income came mainly from the royalties on his already published books and from an advance on his next one (this was eventually to become The Language of Madness). But he couldn’t write. It seemed that the English soil which had produced a burst of creativity in the 60’s had suddenly run dry. Some new spark was needed.

|

|||

My memories of R.D. LaingWritten for International Journal of Psychotherapy, special issue, 2011 Personal recollections of Ronnie Laing EMMY VAN DEURZEN Abstract: This is a very personal account of contact with R.D. Laing and some of the spin-offs of his work into the Philadelphia Association / Arbours Association and anti-psychiatry movement in the 1970s by one of the founders of Existential Psychotherapy in the UK. Key Words: R.D. Laing, personal memories, reflections, existential psychotherapy. I came to the UK in 1977, from France, where I used to work as a clinical psychologist and existential therapist in psychiatric hospitals (though my first training was as a philosopher) in order to work with R.D. Laing. Reading The Divided Self and The Politics of Experience (in French), around 1971, had deeply affected me personally and had impacted greatly on the work I did with psychiatric patients.

I had sought out the Arbours Association[i] therapists when they spoke at a conference in Milan in 1975 and had come over to visit the Arbours Association to see whether it might be of interest to work with the group, and also with R.D. Laing in his Philadelphia Association (PA)[ii]. My ex-husband Jean-Pierre Fabre (a psychiatrist) and myself were promptly invited by Joseph Berke and Morton Schatzmann[iii] to come over to work with the Arbours Association in London, and we accepted their invitation. We moved into an Arbours community house in South London in October 1977 and contributed to the work at the Arbours crisis centre as well. I also started teaching existential therapy on the Arbours training programme, when it emerged that such teaching was not happening, as the Arbours training programme was almost totally based in neo-Kleinian theory at that time. We set up some meetings with Ronnie Laing, with Paul and Carol Zeal, with Francis Huxley, and some others. We started attending some seminars with the P.A. too. But we got the impression from what people told us, and from what we observed for ourselves, that the Philadelphia Association was very run down by then. Several P.A. colleagues warned us not to get too involved, as it was crumbling and had become a ‘toxic’ organization, and Ronnie himself seemed to be in very bad shape. It was also a great disappointment to find that the P.A. was focusing many of its seminars on French psychoanalysis. Since Jean-Pierre and I had both been trained in this way of working for many years in France, and had been fighting the hegemony of Lacanian thinking, and had indeed specifically come to England to get away from all of that, it was rather ironic to be faced with rather poorly formulated French psychoanalytic thinking in the place where we had hoped to connect up with the existential tradition we were interested in. My idea that, coming to the UK, would allow us to work directly with existential therapy, quickly turned out to be illusory and I began to realize that I would actually have to create what I had hoped to find ready-made. Not surprisingly, from the start, my relationship with Ronnie was not a very good one. He certainly at this stage did not like to engage with the critique that I was formulating. It seemed to me that he did not like to be on an equal level with colleagues, and was certainly not very interested in hearing about the rather revolutionary psychiatric and therapeutic work that J-P and I had been involved with in France. Ronnie, it was clear to me, expected to be treated as a guru, and I was certainly not looking for a guru, but for a fair and frank exchange. I remember him shouting at me one day on the phone that he was, “f…ing R.D. Laing and my husband and myself were just some f…ing psychiatrists from France”. With hindsight, it occurs to me that he may have wrongly assumed that we wanted to bring in more French psychoanalysis into the PA. Nothing could have been further from the truth. But his attitude was so haughty, disdainful and rejecting that I decided to steer clear of him as much as possible. I gave it one more shot by attending his infamous lecture on ‘The Politics of Helplessness’ at the Round House, in early 1978, but I found it appallingly prepared, extremely poor in theoretical or practical contents, and completely uninspiring. I was shocked by the way the P.A. trainees were made to sit at his feet, on stage. I knew then for certain that this scene was not for me and that Laing’s work could not truly inform psychotherapeutic practice, but would only lead to un-productive adoration. Ronnie himself seemed burnt out by his own fame and I made a mental note never to let myself become famous, or too enamored with my own ideas or my own importance. Fame, I knew from observing him, corrupts as badly as power or money. Too much light shining on you, blinds you and weakens you. What still sticks in my mind to this day is the story that he told at that conference of two climbers, tied to each other by ropes as they climbed a steep mountain slope, until one of them fell into a precipice, from which the other was unable to hoist him to safety. The question he asked his public was, ‘When do you decide to cut the rope?’ I was shocked by his metaphor for psychotherapy and knew instinctively that this was the wrong question, and a completely wrong image to use. My inner protest against his fatalism and his personal helplessness spurred me on to formulate a much more structured form of existential therapy that could enable others to think for themselves and find their own path, be it with some support. Of course, living in an Arbours therapeutic community, I was only too aware of the impossibility of ‘saving’ other people in such a context, especially if one had to be apologetic about being a ‘therapist’, instead of just being a co-resident. It seemed obvious to me that, going out on a hazardous journey into madness without a compass, a map and some decent safety equipment and sensible planning, was mad indeed and could only lead to accidents. But I carried on with this anti-psychiatric[iv] journey for a little longer yet, to make quite sure it really was the wrong path, and that I wasn’t just being dismissive and arrogant about it. I also felt I had more to learn from the people I lived with. It was through talking with them, and by studying and teaching the philosophical writings of my favourite existential authors, that I began to formulate my own ideas in a systematic way from this point onwards. One could say that my disenchantment with Ronnie catapulted me into my own writing, and released me to be creative in my own right. I carried on seeing Leon Redler for therapy in one of the P.A. communities for a while in 1978, but soon decided to leave the Arbours and the P.A., and in April 1978 went to California to visit various mental health projects and to do some training at the Esalen Institute. Upon my return I got re-involved with the Arbours community in a different capacity, continued teaching for the Arbours training programme and became a supervisor to the trainees. I also, somewhat to my shame, was part of the Laing/Rogers encounter in the London Hilton Hotel in September 1978 and was one of Ronnie’s therapists, in the great rebirthing event on the dance-floor of the Hilton hotel. After that I decided that enough was enough and preferred to continue developing my own work, and I took a job with Antioch University’s London-based MA (Master’s degree) in Humanistic Psychology, which was quite tied in with the P.A. I still attended occasional P.A. meetings and had many students who were in placement either with the P.A., or the Arbours. I also did some yoga-based work with Mel Huxley, and Arthur and Janet Balaskas, around the time my son was born (February 1981). In fact, the night my son was born (more or less exactly thirty years ago at the time of this writing) Janet was going between the Royal Free, where she was my birthing partner and Ronnie’s house in Belsize Park, where she was helping him through a rough time during his marriage break down. I think this was a final confirmation for me that he was losing it and that – in some way – the future of existential therapy was in my hands. I set up the first Masters degree programme based on existential therapy for Antioch University in 1982 and then moved this to Regent’s College, London in 1985, where it grew into an entire school of psychotherapy. During those years of very hard work, raising my young family and establishing a new therapeutic approach at the same time, I lost touch with the Arbours Association, the P.A. and Ronnie Laing. I only really got back in touch properly with Ronnie around the time that I decided to set up the Society for Existential Analysis. This was in 1987, on the strength of me just having completed my first book on Existential Psychotherapy (Existential Counselling and Psychotherapy in Practice, which was to be published by Sage in 1988) and, of which I sent him an early copy. He was much mellowed by that time and I was pleasantly surprised to find that we could talk sensibly about setting up a body for existential therapists to heal the splits between PA, Arbours and the Regent’s College-based programmes. I think Ronnie was quite impressed by what I had been able to achieve at Regent’s College and we discussed various ways in which he might be involved in it. But he did not want to come to the founding meeting of the Society for Existential Analysis and sent John Heaton instead, who kindly proposed me as first chair of the Society, which was duly created together with the Journal Existential Analysis. I had promised Ronnie that though our first conference would be about existential analysis; the second would be about his contribution to psychotherapy and would be entitle ‘Demystifying Therapy’. So, John Heaton and I gave the keynote talks at the first SEA conference in 1988 and Ronnie was nowhere to be seen, but fully expected to be the star turn at the second conference. He was very keen that this second conference should be a platform for him to present some new ideas of his own about his way of doing therapy. I believed that he was actually interested in rising to the challenge that I had put to him to formulate an existential therapy that could be taught to others. But, in the middle of the process of us putting together the programme for that second SEA conference, he tragically died, in August 1989. It was a big shock. The Society members immediately decided that the conference that we had been planning should be about Ronnie Laing and his work, even so, and Adrian Laing, his lawyer son, agreed to be our keynote speaker. Adrian gave a rather bracing and somewhat harsh paper about his father and this caused quite a stir. I think that for me, this was the end of any remaining attachment to Laingian theory and I wrote a paper arguing how much Laing had misunderstood the whole philosophical notion of ontological anxiety. This was later published in my book, Paradox and Passion in Psychotherapy.[v] I am afraid that my recollection of Laing’s work has continued to be more about the ‘shadows’ that he created than about the light that his early work shone on my own life and that of many others. I came to the UK because of his work: no doubt about it. But instead of finding a flourishing existential scene, I found a chaotic situation where those who needed help were being plunged into confusion, rather than into elucidation and enlightenment. The great myth of the breakdown leading to a breakthrough had been shown to be just that: a myth! So, I decided I could do better than that, and worked extremely hard to create the therapy that I had hoped to find in the UK, when I immigrated here in the seventies. I would like to think that my work, in good Laingian tradition, speaks for truth and enables people to find truth where confusion reigned, previously. I know for certain, that creating the Regent’s College[vi] courses and subsequently, and perhaps more importantly, the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling[vii], has allowed existential psychotherapy to become established as a formal, and now well recognized, tradition in the UK (see my book: Everyday Mysteries[viii]). There are now thousands of people in the UK, who have had a structured and formal training in this approach, up to doctoral level. Many countries in the rest of Europe have also created existential training courses on this same model, especially through the work that Digby Tantam, myself and colleagues from other European countries have done in creating the European-funded, online, Septimus courses[ix] in a dozen European countries. Indeed, there is now a sweeping movement in this existential therapeutic direction all over the world. \As I lecture on each continent, I find enthusiasm and dedication to philosophical therapy everywhere. There is something about the approach that allows for a cross-cultural non-doctrinaire take on the world and this is what liberates people to face our global and often paradoxical realities. I think Laing’s work was so popular because it drew on this philosophy of liberation and connected directly with people’s sense of alienation. His early work will continue to be of much interest to many people over the next decades for that reason and he certainly figures prominently on New School syllabi. But it wasn’t Laing’s work, on its own, that created the movement of existential therapy. In terms of actual psychotherapeutic method, his work stopped short of providing any practical guidance for trainees or clients, leaving people to turn to now outdated concepts from psychoanalysis or rebirthing instead. I feel that the hard and ongoing work that many of us have done in creating existential psychotherapy as a distinct approach in the UK will have a much bigger impact and longer lasting effect in the long run. But this is a slow and carefully built impact, and not the flashy, fame-driven bolt of lightning that were the ideas of R.D. Laing. It is the discipline of philosophy that now carries the approach, rather than the emotional passion of one person. Whilst this is every bit as inspirational as were Laing’s words, it takes a lot longer to absorb, fully understand, and apply. Ultimately, it has more therapeutic value and dynamism, as it is not based in wishful thinking, but in reality. While this form of existential therapy is in many ways a testimony to Laing’s brilliant ideas, it unfortunately owes very little to him directly. Author: Emmy van Deurzen is Principal of the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling in London, where she runs several masters and doctoral programmes in existential therapy and counselling psychology, jointly with Middlesex University. She is the author of ten books on existential therapy. E-mail: emmy@nspc.org.uk Endnotes: I had sought out the Arbours Association[i] therapists when they spoke at a conference in Milan in 1975 and had come over to visit the Arbours Association to see whether it might be of interest to work with the group, and also with R.D. Laing in his Philadelphia Association (PA)[ii]. My ex-husband Jean-Pierre Fabre (a psychiatrist) and myself were promptly invited by Joseph Berke and Morton Schatzmann[iii] to come over to work with the Arbours Association in London, and we accepted their invitation. We moved into an Arbours community house in South London in October 1977 and contributed to the work at the Arbours crisis centre as well. I also started teaching existential therapy on the Arbours training programme, when it emerged that such teaching was not happening, as the Arbours training programme was almost totally based in neo-Kleinian theory at that time. We set up some meetings with Ronnie Laing, with Paul and Carol Zeal, with Francis Huxley, and some others. We started attending some seminars with the P.A. too. But we got the impression from what people told us, and from what we observed for ourselves, that the Philadelphia Association was very run down by then. Several P.A. colleagues warned us not to get too involved, as it was crumbling and had become a ‘toxic’ organization, and Ronnie himself seemed to be in very bad shape. It was also a great disappointment to find that the P.A. was focusing many of its seminars on French psychoanalysis. Since Jean-Pierre and I had both been trained in this way of working for many years in France, and had been fighting the hegemony of Lacanian thinking, and had indeed specifically come to England to get away from all of that, it was rather ironic to be faced with rather poorly formulated French psychoanalytic thinking in the place where we had hoped to connect up with the existential tradition we were interested in. My idea that, coming to the UK, would allow us to work directly with existential therapy, quickly turned out to be illusory and I began to realize that I would actually have to create what I had hoped to find ready-made. Not surprisingly, from the start, my relationship with Ronnie was not a very good one. He certainly at this stage did not like to engage with the critique that I was formulating. It seemed to me that he did not like to be on an equal level with colleagues, and was certainly not very interested in hearing about the rather revolutionary psychiatric and therapeutic work that J-P and I had been involved with in France. Ronnie, it was clear to me, expected to be treated as a guru, and I was certainly not looking for a guru, but for a fair and frank exchange. I remember him shouting at me one day on the phone that he was, “f…ing R.D. Laing and my husband and myself were just some f…ing psychiatrists from France”. With hindsight, it occurs to me that he may have wrongly assumed that we wanted to bring in more French psychoanalysis into the PA. Nothing could have been further from the truth. But his attitude was so haughty, disdainful and rejecting that I decided to steer clear of him as much as possible. I gave it one more shot by attending his infamous lecture on ‘The Politics of Helplessness’ at the Round House, in early 1978, but I found it appallingly prepared, extremely poor in theoretical or practical contents, and completely uninspiring. I was shocked by the way the P.A. trainees were made to sit at his feet, on stage. I knew then for certain that this scene was not for me and that Laing’s work could not truly inform psychotherapeutic practice, but would only lead to un-productive adoration. Ronnie himself seemed burnt out by his own fame and I made a mental note never to let myself become famous, or too enamored with my own ideas or my own importance. Fame, I knew from observing him, corrupts as badly as power or money. Too much light shining on you, blinds you and weakens you. What still sticks in my mind to this day is the story that he told at that conference of two climbers, tied to each other by ropes as they climbed a steep mountain slope, until one of them fell into a precipice, from which the other was unable to hoist him to safety. The question he asked his public was, ‘When do you decide to cut the rope?’ I was shocked by his metaphor for psychotherapy and knew instinctively that this was the wrong question, and a completely wrong image to use. My inner protest against his fatalism and his personal helplessness spurred me on to formulate a much more structured form of existential therapy that could enable others to think for themselves and find their own path, be it with some support. Of course, living in an Arbours therapeutic community, I was only too aware of the impossibility of ‘saving’ other people in such a context, especially if one had to be apologetic about being a ‘therapist’, instead of just being a co-resident. It seemed obvious to me that, going out on a hazardous journey into madness without a compass, a map and some decent safety equipment and sensible planning, was mad indeed and could only lead to accidents. But I carried on with this anti-psychiatric[iv] journey for a little longer yet, to make quite sure it really was the wrong path, and that I wasn’t just being dismissive and arrogant about it. I also felt I had more to learn from the people I lived with. It was through talking with them, and by studying and teaching the philosophical writings of my favourite existential authors, that I began to formulate my own ideas in a systematic way from this point onwards. One could say that my disenchantment with Ronnie catapulted me into my own writing, and released me to be creative in my own right. I carried on seeing Leon Redler for therapy in one of the P.A. communities for a while in 1978, but soon decided to leave the Arbours and the P.A., and in April 1978 went to California to visit various mental health projects and to do some training at the Esalen Institute. Upon my return I got re-involved with the Arbours community in a different capacity, continued teaching for the Arbours training programme and became a supervisor to the trainees. I also, somewhat to my shame, was part of the Laing/Rogers encounter in the London Hilton Hotel in September 1978 and was one of Ronnie’s therapists, in the great rebirthing event on the dance-floor of the Hilton hotel. After that I decided that enough was enough and preferred to continue developing my own work, and I took a job with Antioch University’s London-based MA (Master’s degree) in Humanistic Psychology, which was quite tied in with the P.A. I still attended occasional P.A. meetings and had many students who were in placement either with the P.A., or the Arbours. I also did some yoga-based work with Mel Huxley, and Arthur and Janet Balaskas, around the time my son was born (February 1981). In fact, the night my son was born (more or less exactly thirty years ago at the time of this writing) Janet was going between the Royal Free, where she was my birthing partner and Ronnie’s house in Belsize Park, where she was helping him through a rough time during his marriage break down. I think this was a final confirmation for me that he was losing it and that – in some way – the future of existential therapy was in my hands. I set up the first Masters degree programme based on existential therapy for Antioch University in 1982 and then moved this to Regent’s College, London in 1985, where it grew into an entire school of psychotherapy. During those years of very hard work, raising my young family and establishing a new therapeutic approach at the same time, I lost touch with the Arbours Association, the P.A. and Ronnie Laing. I only really got back in touch properly with Ronnie around the time that I decided to set up the Society for Existential Analysis. This was in 1987, on the strength of me just having completed my first book on Existential Psychotherapy (Existential Counselling and Psychotherapy in Practice, which was to be published by Sage in 1988) and, of which I sent him an early copy. He was much mellowed by that time and I was pleasantly surprised to find that we could talk sensibly about setting up a body for existential therapists to heal the splits between PA, Arbours and the Regent’s College-based programmes. I think Ronnie was quite impressed by what I had been able to achieve at Regent’s College and we discussed various ways in which he might be involved in it. But he did not want to come to the founding meeting of the Society for Existential Analysis and sent John Heaton instead, who kindly proposed me as first chair of the Society, which was duly created together with the Journal Existential Analysis. I had promised Ronnie that though our first conference would be about existential analysis; the second would be about his contribution to psychotherapy and would be entitle ‘Demystifying Therapy’. So, John Heaton and I gave the keynote talks at the first SEA conference in 1988 and Ronnie was nowhere to be seen, but fully expected to be the star turn at the second conference. He was very keen that this second conference should be a platform for him to present some new ideas of his own about his way of doing therapy. I believed that he was actually interested in rising to the challenge that I had put to him to formulate an existential therapy that could be taught to others. But, in the middle of the process of us putting together the programme for that second SEA conference, he tragically died, in August 1989. It was a big shock. The Society members immediately decided that the conference that we had been planning should be about Ronnie Laing and his work, even so, and Adrian Laing, his lawyer son, agreed to be our keynote speaker. Adrian gave a rather bracing and somewhat harsh paper about his father and this caused quite a stir. I think that for me, this was the end of any remaining attachment to Laingian theory and I wrote a paper arguing how much Laing had misunderstood the whole philosophical notion of ontological anxiety. This was later published in my book, Paradox and Passion in Psychotherapy.[v] I am afraid that my recollection of Laing’s work has continued to be more about the ‘shadows’ that he created than about the light that his early work shone on my own life and that of many others. I came to the UK because of his work: no doubt about it. But instead of finding a flourishing existential scene, I found a chaotic situation where those who needed help were being plunged into confusion, rather than into elucidation and enlightenment. The great myth of the breakdown leading to a breakthrough had been shown to be just that: a myth! So, I decided I could do better than that, and worked extremely hard to create the therapy that I had hoped to find in the UK, when I immigrated here in the seventies. I would like to think that my work, in good Laingian tradition, speaks for truth and enables people to find truth where confusion reigned, previously. I know for certain, that creating the Regent’s College[vi] courses and subsequently, and perhaps more importantly, the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling[vii], has allowed existential psychotherapy to become established as a formal, and now well recognized, tradition in the UK (see my book: Everyday Mysteries[viii]). There are now thousands of people in the UK, who have had a structured and formal training in this approach, up to doctoral level. Many countries in the rest of Europe have also created existential training courses on this same model, especially through the work that Digby Tantam, myself and colleagues from other European countries have done in creating the European-funded, online, Septimus courses[ix] in a dozen European countries. Indeed, there is now a sweeping movement in this existential therapeutic direction all over the world. \As I lecture on each continent, I find enthusiasm and dedication to philosophical therapy everywhere. There is something about the approach that allows for a cross-cultural non-doctrinaire take on the world and this is what liberates people to face our global and often paradoxical realities. I think Laing’s work was so popular because it drew on this philosophy of liberation and connected directly with people’s sense of alienation. His early work will continue to be of much interest to many people over the next decades for that reason and he certainly figures prominently on New School syllabi. But it wasn’t Laing’s work, on its own, that created the movement of existential therapy. In terms of actual psychotherapeutic method, his work stopped short of providing any practical guidance for trainees or clients, leaving people to turn to now outdated concepts from psychoanalysis or rebirthing instead. I feel that the hard and ongoing work that many of us have done in creating existential psychotherapy as a distinct approach in the UK will have a much bigger impact and longer lasting effect in the long run. But this is a slow and carefully built impact, and not the flashy, fame-driven bolt of lightning that were the ideas of R.D. Laing. It is the discipline of philosophy that now carries the approach, rather than the emotional passion of one person. Whilst this is every bit as inspirational as were Laing’s words, it takes a lot longer to absorb, fully understand, and apply. Ultimately, it has more therapeutic value and dynamism, as it is not based in wishful thinking, but in reality. While this form of existential therapy is in many ways a testimony to Laing’s brilliant ideas, it unfortunately owes very little to him directly. Author: Emmy van Deurzen is Principal of the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling in London, where she runs several masters and doctoral programmes in existential therapy and counselling psychology, jointly with Middlesex University. She is the author of ten books on existential therapy. E-mail: emmy@nspc.org.uk Endnotes:

[i] Arbours Association: http://www.arboursassociation.org

[ii] Philadelphia Association: http://www.philadelphia-association.co.uk

[iii] Joseph Berke & Morton Schatzman – colleagues of R.D. Laing at Kingsley Hall and founders of the Arbours Association.

[iv] The movement that started in the UK around the work of R.D. Laing and David Cooper was sometimes known as the ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-psychiatry

[v] van Deurzen, E. (1998). Paradox and Passion in Psychotherapy: An existential approach to therapy and counselling. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

[vi] Regent’s College: http://www.regents.ac.uk

[vii] New School for Psychotherapy & Counselling: http://www.nspc.org.uk

[viii] van Deurzen, E. (2000). Everyday Mysteries: Existential Dimensions ofPsychotherapy. Hove: Routledge.

[ix] SEPTIMUS (Strengthening European Psychotherapy Training through Innovative Methods and Unification of Standards) courses: see http://www.europsyche.org/contents/13120

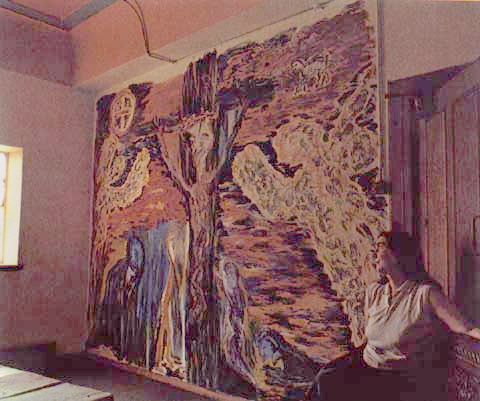

05 NOV–08 JAN 2011 MARY BARNES In 1965 radical psychiatrist R.D. Laing co-founded an experimental therapeutic community at Kingsley Hall in Bow, East London. Presenting herself on the brink of a serious mental breakdown, Mary Barnes (1923-2001) was Kingsley Hall’s first resident. Under the guidance of Laing and his colleagueJoseph Berke, Barnes underwent a near total behavioral regression. Refusing to eat, dress or wash, she was in her own words “going down.” Around this time she produced her first artwork – a pair of black breasts painted on the wall of her room in her own shit. Focusing principally on her time at Kingsley Hall (1965-70), Mary Barnes presents painting, drawing, sculpture and writing produced by Barnes alongside an extensive archive of documents, films, audio recordings and photographs relating to her work and the legacy of R.D. Laing’s thought. Accompanying the main exhibition will be a cycle of films. These include Abraham Segal’s Coleurs Folie(1986) and Asylum (1972) Produced and Directed by Peter Robinson. (Asylum by permission of Surveillance Films).

by Mary Barnes and Joseph Berkes Other Press, 2002 Review by Tony O’Brien, M.Phil on Feb 24th 2005 Mary Barnes’ autobiography is one of the frankest and most literal accounts of madness you are likely to read. From her description of her early family life to the sometimes tediously detailed description of her day to day experience of regression into psychosis, Barnes spares herself and the reader little. Interspersed with sections by her therapist, Joseph Berkes, and with new epilogues added since the publication of the 1971 edition, the book spans the entire period of Barnes’ life until her death in 2001. Barnes’ story is not simply an autobiography, but a first-person account (two if you include Berkes’) of a tumultuous time in British psychiatry. The asylum era had faltered under the weight of internal critique, public distrust, and the seemingly limitless capacity of society to consign the mentally ill to institutions. New theories of mental illness, especially schizophrenia, were emerging. In particular, psychoanalytically oriented theorists were looking at the role of the family in schizophrenia. Thus Barnes’ personal life history followed a path toward, and then away from the mainstream of British psychiatry. Barnes begins with the ironic comment: ‘My family was abnormally nice’. From there she recalls a childhood under the austere gaze of her mother, and her struggle to live with the conflicts carried into her adult life. She recounts early experiences of her reaction to her mother’s pregnancies, and her sense of rejection, displacement and rage. Trained as a nurse, and for a time employed teaching nursing, Barnes’ life does not show the trajectory of adolescent role failure often considered to characterize schizophrenia. Her conversion to Catholicism showed a concern with questions of meaning that were later to assume almost mystical proportions. According to her account Barnes achieved considerable success professionally, but remained troubled by self doubt and at times delusional ideas about herself, her family, and her effects on the world around her. These led to hospital admissions and intervention with the standard treatments of the time, ECT and chlorpromazine. When she met R.D Laing her life changed, and it is here that the biography takes on and additional social and historical interest. In 1965 Barnes entered Kingsley Hall, a therapeutic community set up by antipsychiatrists Laing and Esterson. The mood was radical; the techniques primitive and untried. Laing considered psychosis to be a healing experience which, fully experienced would bring about its own resolution. Laing was the enfant terrible of British psychiatry in the 1960s. His somewhat precocious The Divided Self set out what he saw as the basis for an alternative scientific account of schizophrenia, that of schizophrenia as an indicator of pathological family interaction. Kingsley Hall was the crucible in which Laing’s ideas would be tested. Barnes would become one of Laing’s ambassadors; a voyager into the depths of psychosis, who would emerge to explain its mysteries to those who would listen. A lot of people listened. Kingsley Hall, during the time of Mary Barnes residency, became a magnet for radical thinkers in psychiatry. Visitors included Fritz Perls and Loren Mosher. As mainstream resistance to Laing’s ideas became more entrenched, his critique took on an explicit political dimension through his identification with concerns of emancipation and liberation, rather than merely the alleviation of distress. JERVIS E IL CONVEGNO SU BASAGLIA (1 – L’esperienza di Gorizia)

– 16 GENNAIO 2013PUBBLICATO IN: PERSONAGGI

Che certe polemiche tra Jervis e l’area basagliana di “Psichiatria democratica” esistessero da tempo era cosa nota e che non si fossero mai sopite del tutto ha trovato ampia conferma proprio dopo la pubblicazione de “La razionalità negata” che le ha acerbamente disseppellite, rimettendo evidentemente il “dito sulla piaga” di un nervo scoperto. Non mi aspettavo certo sviolinate d’amore verso Jervis, ma quello che dalle loro risposte mi ha colpito è stato l’eccessivo livore, rabbia e rancore contro di lui; non è uscita fuori la fatidica parola ma il senso intuibile era quello di essere considerato un “traditore” della causa, l’unico vero “sabotatore“ dell’esperienza idilliaca di Gorizia. Come già accennato, gli attacchi sono stati portati particolarmente al libro di Jervis “Il buon rieducatore”(1977) che a detta dei relatori (sui cui nomi preferisco tacere) ha segnato anche una frattura personale con Basaglia, e manco a dirlo al già citato Jervis-Corbellini “La razionalità negata. Psichiatria e antipsichiatria in Italia” (2008). Gli attacchi che hanno sfiorato anche il cattivo gusto del pettegolezzo e perfino della denigrazione inventata contro Basaglia, mi hanno fortemente insospettito come se ci fosse nei confronti di Johnny il sentimento ambivalente di chi, mentre rimprovera implacabilmente, vive la cocente delusione dell’abbandono. Le parole di uno dei relatori risuonavano, infatti, come un monito nostalgico di rimprovero per non essere lì in mezzo a loro (magari lo potesse, aggiungo io!), riconoscendogli quell’immensa cultura che li avrebbe certamente aiutati. Il convegno è poi scivolato verso altri temi. Tornando a casa, ruminavo tra me e me su quanto accaduto e per quanto potessi essere stato io a somministrare la pastura non riuscivo a digerire il pasto indigesto. Mi sono preso la briga di andare a riprendere “Il buon rieducatore” dove nel primo capitolo intitolato proprio “Il buon rieducatore” c’è, oltre che una piacevole autobiografia fino a quel momento, anche un ottimo resoconto dell’esperienza di Gorizia. Il primo capitolo che vale come lunga introduzione data dicembre 1976, quando lui è già a Reggio Emilia a dirigere i Centri d’igiene mentale, mentre il libro viene edito nel 1977. Questo è quanto scrive Jervis su Basaglia: “Quanto alla mia carriera, avevo chiesto e ottenuto da Basaglia il suo formale e personale impegno che, nel caso l’equipe goriziana si fosse sciolta o trasferita io sarei stato il primo tra i suoi collaboratori a cui egli avrebbe trovato dignitosa sistemazione altrove (…) Rispetto a come si presentavano gli altri direttori di istituti universitari e manicomiali italiani, si misurava subito una netta differenza di qualità. Egli proveniva da una ricca famiglia veneziana, e traeva dalla sua origine aristocratica e alto borghese doti di gusto, cultura, spregiudicatezza, attitudine al comando, disprezzo per gli eufemismi e per le piccolezze quotidiane. Leggeva, e a quanto mi disse i suoi autori preferiti erano Pirandello e Sartre; amava molto occuparsi di mobili antichi, era un antifascista e progressista; inoltre, era un uomo simpatico, e viveva in una splendida casa con due figli e una moglie bella e intelligente, Franca Ongaro, che gli faceva da segretaria e lo aiutava a scrivere gli articoli. Infine era ambizioso e sembrava aver fatto di Gorizia lo scopo della sua vita…Con una rabbia e un coraggio di cui credo nessun altro sarebbe stato capace in Italia in quegli anni, in una situazione locale culturalmente e politicamente sfavorevole, aveva deciso di farne un’esperienza pilota. Aveva mantenuto rapporti molto stretti col suo vecchio professore che andava a trovarlo a Padova tutte le settimane, ma si considerava, ed era un outsider; e se da un lato il modello a cui Gorizia si riferiva era quello delle comunità terapeutiche britanniche (che Basaglia aveva visitato), da un altro lato era chiaro che si era trattato sin dall’inizio di un’esperienza dotata di caratteristiche originali. Di fatto Gorizia finì per essere qualcosa di più di una copia di modelli stranieri: divenne un tentativo di detecnicizzare e depsichiatrizzare il rinnovamento manicomiale; fu un luogo di elaborazione di importanti proposte politiche e culturali; e infine assunse una importanza centrale per il rinnovamento della psichiatria istituzionale italiana dopo il 1967”. (Jervis “Il buon rieducatore”,1977, pp.19-20). Una descrizione molto simile si ritrova anche in Jervis-Corbellini “La razionalità negata. Psichiatria e antipsichiatria in Italia”, 2008, pp.82-83. E ancora sulla personalità di Basaglia e i rapporti tra i membri del gruppo goriziano: “Basaglia richiedeva ai suoi collaboratori una adesione incondizionata, e non tollerava facili dissensi teorici e di linea, che tendeva a vivere drammaticamente come attacchi personali. Prima del mio arrivo, il gruppo dei medici allora intorno a Basaglia aveva conosciuto liti, scismi, espulsioni ed emarginazioni; mi resi conto rapidamente che anche nel gruppo attuale vi erano competitività e malumori che appesantivano molto il lavoro. E il lavoro era di per se molto, e pesante, sia come ore che come impegno: io tra l’altro ero tenuto a fare, in quanti medico di sezione, frequentissimi turni di guardia, di 24 o (nei fine settimana) di 48 ore, da cui erano invece esentati sia il direttore che i primari(…) “L’istituzione negata” fu, almeno secondo l’impressione che mi fece allora, una mescolanza quasi inestricabile di esaltazione comunitaristica e “antiautoritaria” e di attenzione critica ai problemi politici e culturali in gioco. I lavori di elaborazione collettiva di quel libro segnarono l’inizio della spaccatura dell’equipe e di una serie di dissensi che, apparentemente legati a rivalità ed esacerbate ambizioni personali, nascondevano invece profonde differenze di linea, e quindi divergenze di scelte operative, Dopo il maggio ’68, a Gorizia come altrove la spaccatura divenne drammatica e irreversibile.”(Jervis “Il buon rieducatore”, 1977, pp. 20-22). Ancora su Basaglia e i rapporti col gruppo: “Da anni Basaglia parlava di lasciare Gorizia (già nel ’66 e’67 pareva che avesse la possibilità di andare a lavorare prima a Ravenna e poi a Bologna). Nel ’68 si sommarono a questo la sua delusione per i dissensi sempre più profondi che dividevano tra loro vari membri dell’equipe, e lui dall’equipe; e la convinzione che l’esperienza goriziana fosse ormai giunta a un punto massimo di sviluppo: in pratica, a un punto morto. Retrospettivamente, sono ora portato a credere che avesse più ragione di quanto non pensassi a quell’epoca: è possibile che l’esperienza goriziana avrebbe avuto la possibilità di progredire ulteriormente, oltre la fase volontaristica dell’ ”ospedale aperto”, solo se all’interno dell’equipe si fosse cessato di ignorare la necessità di un confronto con problemi tecnico-scientifici di tipo più specificamente psichiatrico, come quelli di natura psicoanalitica, o attinenti alle dinamiche di gruppo; oppure se l’istituzione avesse avuto la possibilità di aprirsi all’esterno, di legarsi ai problemi della popolazione locale, di portare “nel territorio” le contraddizioni, i problemi che venivano gestiti invece esclusivamente all’interno delle sue mura. Dall’altro lato, almeno per quanto riguarda quest’ultimo punto, la situazione politica locale e l’ostilità dell’amministrazione provinciale, avrebbero reso difficile, se non quasi impossibile, un sistematico “lavoro all’esterno”: però né allora né, credo, in seguito Basaglia dimostrò interesse per le istanze di base e per la politica “dal basso”, per cui non ritenne che questo costituisse un possibile terreno operativi (…) Un episodio fu indicativo, ed emblematico del clima che si era creato. Quando all’epoca scrissi per i “Quaderni piacentini” un articolo di denuncia sul caso Braibanti-Sanfratello in cui criticavo due cattedratici e ospedalieri di psichiatria fra i più reazionari (Rossini di Modena e Trabucchi di Verona) Basaglia pretese che censurassi il mio scritto o addirittura che, a cause di quelle critiche contro i suoi colleghi, io non lo pubblicassi; alla fine acconsentì solo perché mi impuntai, ma a condizione che al posto del mio nome usassi uno pseudonimo. Così feci con imbarazzo, e firmai con un altro nome. In quella circostanza misurai la mia dipendenza oggettiva, istituzionale (ma in parte anche psicologica) dal direttore dell’ospedale: malgrado il clima informale, amichevole e solidale, e malgrado il sentirci “tutti nella stessa barca” (e in parte proprio per questo) la direzione di Basaglia era sostanzialmente autoritaria. Erano a quell’epoca sempre scontri interni: per motivi di disciplina di gruppo, in cui credevo, e di solidarietà, evitai sempre finché rimasi a Gorizia, e anche per vari anni in seguito, di partecipare o anche di far trapelare all’esterno queste divergenze (che erano sempre, in ultima analisi, profonde divergenze politiche ed anche etiche) e di provocare un confronto pubblico sulle differenze d’impostazione e di linea che esistevano fra il mio operare, quello di Basaglia, e quello degli altri membri dell’equipe. Il fatto di non aver reso pubblici i dissensi, e di non aver confrontato apertamente fin dall’inizio le nostre rispettive posizioni con gli ambienti della sinistra e con tutti coloro che guardavano con simpatia all’esperienza goriziana fu indubbiamente un grave errore politico, che produsse confusioni e danni…Del resto moltissimi del vasto pubblico non volevano sentir parlare di dissensi di linea né di diversità di condotta: il gruppo goriziano fu idealizzato dai suoi simpatizzanti come politicamente omogeneo (cosa che invece non fu mai) o venne identificato con formule “antipsichiatriche” più o meno semplicistiche. Del resto credo che il pubblico avesse tutte le ragioni per non voler sentir parlare di dissensi, dal momento che questi ultimi sembravano riconducibili solo a beghe personali”.(Jervis “ Il buon rieducatore,1977,pp. 23-25). L’episodio che si riferisce al caso Braibanti-Sanfratello è riportato con maggiori dettagli anche in Jervis-Corbellini “La razionalità negata. Pschiatria e antipsichiatria in Italia”, 2008, pag.114. Questo è quanto scrive Jervis verso la fine dell’esperienza goriziana: “ Ma vorrei tornare ai fatti di quell’epoca, cioè all’estate del ’68. La tesi di Basaglia non era solo che l’esperienza di Gorizia fosse finita (e già su questo punto il resto dell’equipe non era d’accordo) ma altresì (per usare un’espressione che ripeteva spesso) occorresse “riconsegnare Gorizia agli psichiatri”: cioè andarsene tutti, e trasformare di nuovo l’ospedale aperto in ospedale chiuso, chiamando a gestirlo un direttore tradizionalista e medici conservatori; e cercare di far carriera altrove (…) ma egli si scontrò soprattutto con l’opposizione di Pirella. Con molti buoni argomenti e molta fermezza, Pirella dichiarò che non contestava affatto a Basaglia il diritto di lasciare Gorizia se lo desiderava: ma che riteneva giusto, anche per i ricoverati e gli infermieri , che l’esperienza continuasse. In quanto membro più anziano e di più alto grado dell’equipe se la sentiva di assumere la direzione dell’ospedale, lavorare con altri, andare avanti. Su questo contrasto io persi una buona occasione per dimostrarmi quel gran nemico dell’opportunismo, che spesso lasciavo intendere di essere: trovavo che Pirella aveva ragione ma all’inizio non lo dissi con chiarezza, per non rovinarmi definitivamente i rapporti con Basaglia. (Ciò non mi servì neppure, perché ne aveva più che abbastanza della mia collaborazione, tanto che mi impedì di occupare un posto messo a concorso nel manicomio di Parma, e mi disse chiaro e tondo che per il mio futuro professionale e di lavoro vedessi di arrangiarmi. Quanto a lui , ammaestrato dall’esperienza, per il suo futuro sarebbe stato attento a scegliersi collaboratori “più giovani e più di buon carattere”). La direzione di Gorizia fu dunque presa da Pirella, con cui rimasi a lavorare. Però Basaglia non digerì molto bene l’idea che esistesse una “Gorizia senza Basaglia”. In Italia e anche nel mondo si sparse a quell’epoca la voce, totalmente falsa, secondo cui egli era stato costretto ad andarsene per l’opposizione degli ambienti politici retrivi o per persecuzioni giudiziarie, tanto che l’esperienza goriziana pareva fosse finita nella repressione; e non riuscii mai a capire fino a che punto Basaglia stesso contribuisse a fabbricare e propagare queste dicerie. Quando nell’autunno del ’69, ormai stabilitomi a Reggio Emilia, ottenni udienza dal ministro della Sanità (a quell’epoca, Ripamonti) per avere il riconoscimento ministeriale dell’attività appena iniziata dei Centri di igiene mentale di Reggio, fui interrogato con molta cortesia e simpatia sulla sorte dell’esperienza goriziana: il ministro mi chiese se a Gorizia vi erano grosse difficoltà, e se proprio non poteva fare qualcosa, anche finanziariamente; risposi che non solo l’esperienza non aveva fatto passi indietro, ma stava procedendo, ora soprattutto grazie agli sforzi di Pirella e Casagrande, e che un suo aiuto sarebbe stato molto importante, forse decisivo. Il ministro parve imbarazzato; poi mi disse che era disorientato, perché Basaglia in persona gli aveva risposto poco tempo prima che l’esperienza di Gorizia era “del tutto chiusa e conclusa”, e che non era proprio il caso di aiutarla. In seguito i rapporti tra Basaglia e Pirella migliorarono sensibilmente, e fra gran parte dell’equipe goriziana si cementarono nuovi accordi. Io non rivelai mai l’episodio del ministro.” (Jervis“ Il buon rieducatore”,1977, pp.25-26). Eviterei di commentare oltre misura questi passi (sarebbe fin troppo facile!), mi limito a dire che sulla scia dell’atteggiamento umano-scientifico profondamente antidogmatico che proprio Jervis ci ha insegnato, quanto riportato non va certamente preso (anche da coloro che lo hanno amato) come l’oro colato della “verità”, ma sicuramente come l’ ”esperienza” umana e professionale dello stesso Jervis che risulta però profondamente “diversa” da quanto riportato al convegno. Anche nel prossimo articolo continueremo a parlare del convegno, ma centrato di più sul tema psichiatria-antipsichiatria. BIBLIOGRAFIA -G.Jervis “Il buon rieducatore”, Feltrinelli, Milano, 1977 -G.Corbellini- G.Jervis” La razionalità negata. Psichiatria e antipsichiatria in Italia, Bollati Boringhieri, Torino, 2008

|

|||

JERVIS E IL CONVEGNO SU BASAGLIA (2 – L’antipsichiatria)– 28 GENNAIO 2013PUBBLICATO IN: PERSONAGGI  L’ultimo capitolo de ”Il buon rieducatore” s’intitola il “Mito dell’antipschiatria”. Qui sono già evidenti le “differenze” con la cosiddetta antipsichiatria da cui Jervis intende prendere le distanze, non solo dal punto di vista tecnico-scientifico, ma più profondamente dal punto di vista politico. Vediamo cosa scrive in proposito: L’ultimo capitolo de ”Il buon rieducatore” s’intitola il “Mito dell’antipschiatria”. Qui sono già evidenti le “differenze” con la cosiddetta antipsichiatria da cui Jervis intende prendere le distanze, non solo dal punto di vista tecnico-scientifico, ma più profondamente dal punto di vista politico. Vediamo cosa scrive in proposito: